Notes de lectures

BEN-ZION: My mother was a very very very fine person not because she was my mother. Because she comes from a very beautiful place in the Ukraine. Some of the biggest and oldest forests in Europe were so wild and so tall that they had in this forest pre-historical all kinds of things which you don't see in any other forest. For instance here they had the big ox they destroyed him so terribly here in America.

MS. SHIKLER: Are you speaking of trees in the forest or are you speaking of something else?

BEN-ZION: The big ox in the forest that used to be that they destroyed here in America the buffalo, and there they had the things which is also an animal but prehistoric too. It was called a jugar. Do you know the word "jugar"?

MS. SHIKLER: No.

BEN-ZION: Yes, you are probably thinking of them as jubuska-do you know jubuska?

MS. SHIKLER: I do not . It sounds like the vodka that I know.

[Audio break.]

...

MS. SHIKLER: Do you remember any significant way he had of expressing himself? Any thing that stands out in your mind?

BEN-ZION: He was very quiet ; he didn't talk much. And because of that, people thought different things. A man keeps quiet, he thinks very deep; it just makes them believe in something. Between those two things-

MS. SHIKLER: So you're saying, in a sense, when a man is quiet people assume that he is very deep, or pretending. Now, which do you think that it was with Rothko?

BEN-ZION: With Rothko, it was different than later, because he really didn't talk.

MS. SHIKLER: He really didn't talk at all? People have said that he had a very intellectual, sophisticated turn of mind.

BEN-ZION: Yes. When he got very drunk. When he got very drunk he could be a little-not pleasant. But that 's all.

MS. SHIKLER: But that wasn't usually the case?

BEN-ZION: No, that wasn't.

MS. SHIKLER: Did you see him drunk often?

BEN-ZION: No. I didn't see him too often. We saw each other pretty often when we had the group. Every year we had a place to exhibit together. None of us had money to buy drinks [laughs].

MS. SHIKLER: When you went t o lunch, what did they serve you, do you remember?

BEN-ZION: I can't recall.

MS. SHIKLER: Was there a lot of furniture around?

BEN-ZION: No.

MS. SHIKLER: Pictures?

BEN-ZION: Pictures, yes.

MS. SHIKLER: Open and showing?

BEN-ZION: Hung up. Every artist used to have them. You know, one artist from Russia, [David ? ] Burliuk-were you ever in his house?

MS. SHIKLER: No.

BEN-ZION: Pictures under the bed, pictures on top of the bed, pictures under the table where they eat. All over.

MS. SHIKLER: Was that true of Rothko too?

BEN-ZION: No, he didn't paint much. One thing which really I wonder about Rothko, which is a hard problem to understand-and I'll tell you what it is. It 's a very import ant problem. We were together about six or seven years as a group, and we exhibited together. Each one, we decided, should participate-to have one or two paintings for the show but to have it in time, to be able to be ready the show nicely. He was always late, bringing his painting which wasn't yet finished.

...

MS. SHIKLER: Mr. Ben-Zion, I'm going to ask you one more question about Rothko before we go on to discuss your experiences with the Jewish Museum. Did you have discussions with Rothko about world affairs? Would you have described him as a pacifist ?

BEN-ZION: No, we don't talk about that, although we knew that some of the group members-most of the members of the artist s' [group] were either the Communist or-but in the group, although we know that one or two belong to the Communists, we didn't discuss it .

BEN-ZION: No, we don't talk about that, although we knew that some of the group members-most of the members of the artist s' [group] were either the Communist or-but in the group, although we know that one or two belong to the Communists, we didn't discuss it .

MS. SHIKLER: You didn't discuss world affairs, for instance.

BEN-ZION: No.

MS. SHIKLER: And he never spoke about the Holocaust, or the Jewish situation? Or, pre-Holocaust, actually - did he speak about the Nazis or Germany?

BEN-ZION: No.

MS. SHIKLER: Okay. In t hat case, I think what we're going to do is put away the question of Rothko, and come back to...

...

MS. SHIKLER: That's a highway. The big picture that we spoke of earlier-what is the name of it ?

|

| Paysan et sa femme, 1964, fer |

MS. SHIKLER: You tell me.

BEN-ZION: King Solomon and Queen of Sheba. She was a Negro.

MS. SHIKLER: It 's a picture of Sheba on the right and Solomon on the left, and their hands are joined.

BEN-ZION: I don't know if t hey are joined.

MS. SHIKLER: She's holding his wrist.

BEN-ZION: Some way of getting in touch.

MS. SHIKLER: When did you paint Solomon and Sheba?

BEN-ZION: This was four years ago.

MS. SHIKLER: You were telling me a very nice story, off tape, about how you decided to return to your writing, and what happened when you went to Israel to find your old friends. I wish you would tell it again, for the tape.

|

| Don Quixote, 1964, fer |

BEN-ZION: It 's hard to tell it. One day.

MS. SHIKLER: How often do you go to Israel?

BEN-ZION: Not very often. I had an opportunity to go, because I had about three big shows in the Maritime Museum [in Haifa]. Then I had three big shows of my etchings in the Jerusalem Museum. And then I had some ot her shows.

...

BEN-ZION: Now I see very little people, because I am very busy with my literary work now. They published a lot. In t he last two and a half years they published 14 books.

MS. SHIKLER: That's a lot of books.

BEN-ZION: And they keep on going. So I'm very-writing is a very-especially to a man like me that didn't write for so many years and likes to catch up.

MS. SHIKLER: What stimulates an idea for a book, for your writing? What starts you off?

|

| Baal Chem Tov, 1970, huile sur toile |

BEN-ZION: This I don't know myself. Many times I didn't know even that I wrote it ; I got into it so casually. It develops so casually that suddenly there it is.

MS. SHIKLER: And you are published almost exclusively in Israel, is that correct ?

BEN-ZION: Yes. I gave you one book in English. Now there's another book being printed in English, too; and I will give you one.

MS. SHIKLER: I'd like that very much.

Transcript from tape-recording, august-september 1982

Realised in the framework of a program by the National Park Service (USA)

Pics are from POBA

Thanks to them

|

| Portrait de Velimir Khkebnikov par Volodymyr Bourliouk, 1913 |

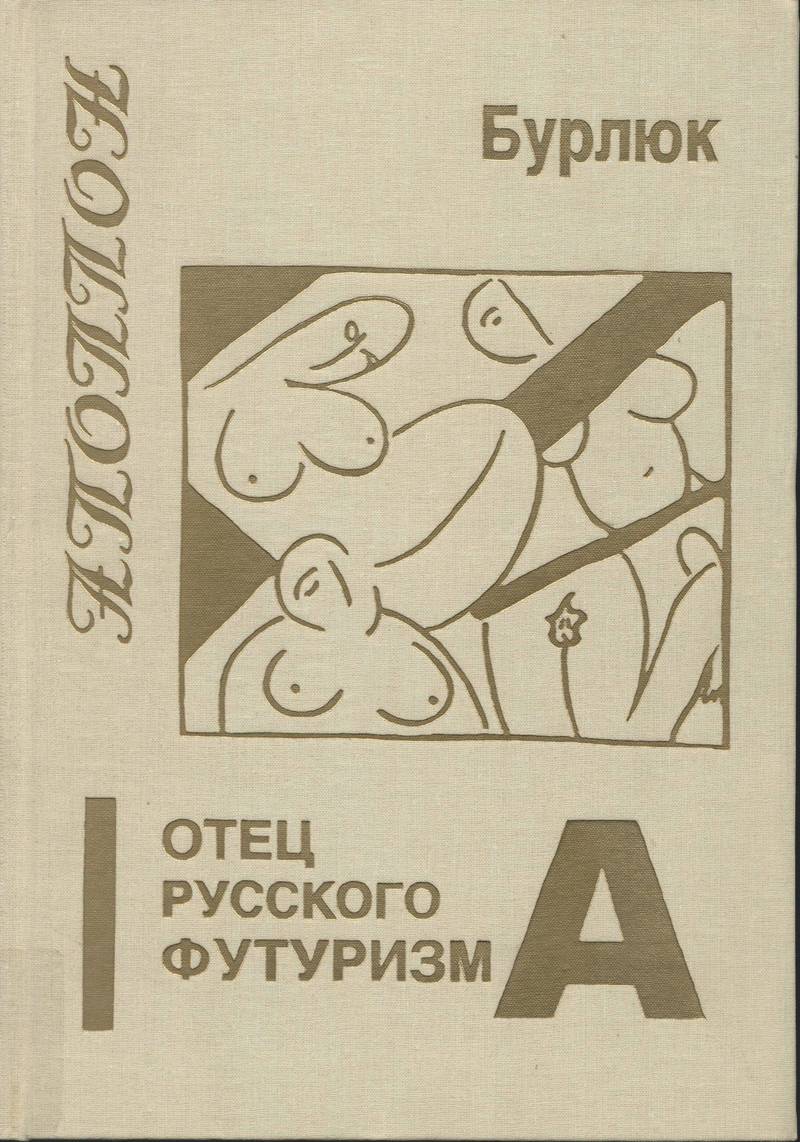

P.S. Ah si, des Oukraïniens, les Bourliouks.

|

| David Bourliouk, Les Oukraïniens, 1912 |

Et même nationaliste oukraïnien le "père du futurisme russe". Selon les critères français. A savoir qu'est reconnu nationaliste oukraïnien tout Oukraïnien qui s'obstine à ne pas vouloir être "russe". Et qui, dès lors : Petliouriste, Bandériste, Mazepiste (terme injustement tombé en désuétude)... Ainsi, curiosité française : Nestor Makhno nationaliste oukraïnien.

Quant à être "from". Tout de même. David Bourliouk avait aménagé sa modeste demeure de 2116 Harrisson Ave, New York, USA, encombrée de tableaux, de peintures, de dessins, de sculptures, de collage, de tout le bric-à-brac boheme d'usage... après un séjour de plusieures années au Japon, il me semble. An artist from Japan.

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire